My new novel, Hinterland, will be released on July 3, 2017, published by UQP.It is already attracting good reviews. This one, in advance of publication, is from Bookseller+Publisher: 'A small Queensland town is divided. The collapse of local industry in a once-thriving dairy community has seen farmland abandoned, repurposed for suburban sprawl or replanted by conservationists. When a government-backed plan to build a dam in the hinterland starts to gain support (and vehement opposition) from locals, tempers and old resentments start to simmer. Hinterland is Steven Lang’s third novel. It is stunning: a love story to the land and a tense exploration of the divisions arising from political alliances, personal beliefs and inherited ideals. Lang’s descriptions of the landscape are beautiful, evoking a stunning visual backdrop for the small hinterland town. His characters are vivid, revealing a true sense of their past and current allegiances, transgressions and ambitions. Glimpses of the past are cleverly interwoven with present events to create a rich narrative for each of the central players. As the novel reaches its dramatic pinnacle, where eco warriors face off against a misguided home-grown militia, it draws together themes of loss, death, rebirth and hope. Fans of Tim Winton’s Dirt Music and Lang’s previous novels, An Accidental Terrorist and 88 Lines about 44 Women, will find much to enjoy in his latest effort.' Kate Frawley is a bookseller and the manager of the Sun Bookshop. I'll be the guest at an Outspoken event on July 14 in Maleny, being interviewed by the wonderful Kate Evans from ABC Radio National's Books and Arts Daily and Books Pulse. The Outspoken website is here.

Spectre2015 Directed Sam MendesThe new Bond opens on the Day of the Dead in Mexico City, with tens of thousands of masked people in the streets, with music, drumming, elaborate floats, men in black suits with white skeletons drawn on their backs, women in flowing Latin dresses. Bond is, of course, in the middle of this, with a beautiful woman, although we only find this out - that the person we are following (who is following someone else) is Bond, and that the woman is beautiful - when they get to their hotel room and de-mask. Perhaps, we think, she thinks, they will now make love. It is not to be. In one of the finest and most understated takes in the whole film Daniel Craig climbs out of the window, walks along the very edge of the parapets of several tall buildings, the revelry continuing, vertiginously, several stories below. He’s carrying an unusual kind of automatic weapon. He moves with ease and grace. He’s not being chased or chasing, just travelling to his destination, oblivious to the danger. You don’t need to know more. Suffice to say there will be explosions, collapsing buildings, helicopters. All before the credits. In many ways this opening sequence is the best part of the film – which is not to say that there are not some delightful set pieces, that the film is not entertaining – it’s just that, at this stage, there is no plot, the only narrative we have is Bond’s casual ease with heights, his singular poise and purpose, his actions in defence of innocent people, and this gives the scene a freedom which the rest of the film would dearly love to have, weighed down, as it is, by clumsy sub-plots, vendettas, old alliances and new loves.Let me declare my biases: I like Bond films. I particularly like Daniel Craig as Bond. When, in Skyfall – once again in an opening sequence – he boards the train, protects himself from being shot by climbing into the cabin of a front-end loader on a float car and then, miraculously, delightfully, thwarts his enemy’s ploy of disengaging the railcars by grabbing the carriage in front with the arm of the aforementioned metallic beast, ripping half its roof off in the process, when he has crawled up the arm and dropped down into the passenger car, full of tremulous innocents, he straightens up, stops for a moment. He stops to adjust his jacket and to shoot his cuffs. Only then does he leap forward to continue pursuing his enemy. That moment is, in my mind, worthy of the whole rollicking, enormous, over-priced, over-blown, worn out franchise.The problem with that film, Skyfall, and, even moreso, with Spectre, and I think I can talk about this without giving spoilers, is that the plots are asinine. Not because Bond survives where several hundred others (including the arch-enemy and a couple of beautiful women) die. That’s never really been the issue; we’re in the business here of the voluntary suspension of disbelief. The problem is that the stories have become centred around Bond himself. The evil genius who is bent on world domination, in these new iterations, is not surprised or even dismayed to find Bond at his heels, interfering with his plans. Bond is, rather, at the centre of his plans. Bond is his raison d’etre, Bond is the kernel of pain at the core of his existence. Elaborate back stories are woven to create this, adoptions, substitutions, mentorships. But this focus on him as the familial member who must be overcome on the path to world domination – as if, in fact, world domination is secondary to humiliating Bond, detracts from the enjoyment in the films in such a profound way that it is all but impossible to put disbelief aside.I don’t want to discover that Bond knew the arch-villain when they were children and one or other of them offended someone. I couldn’t give a rat’s arse to be honest. I’m not in the cinema for a psychological assessment of childhood hurt and how it has given rise to the present villain or the present Bond, I’m there to be blown away by the sheer grandiose hubris of the villain’s plans, his or her delusions of grandeur which should be, it must be said, fantastic, overblown, and slightly scary. I’m here to see Bond, against all odds, foil these plans and rescue the girl (although, it must be said, in this new film the girl has at least some agency, which is a great relief).What has happened recently in the series is that the requirement for an ‘origin story’ has overtaken the genre under the rubric of what Hemingway referred to as ‘the trauma theory of literature’. As I said a moment ago, who cares? Bond films are not literature and we don’t want this guff pasted on them in the hope of making them so. Bond is not a character we love because he was badly treated as a child. We love him because he knows how important it is to be well dressed when dropping into a train carriage, or going into a bar, a ballroom, or a battle. Cut the nonsense please, and give us some real nonsense instead.

In many ways this opening sequence is the best part of the film – which is not to say that there are not some delightful set pieces, that the film is not entertaining – it’s just that, at this stage, there is no plot, the only narrative we have is Bond’s casual ease with heights, his singular poise and purpose, his actions in defence of innocent people, and this gives the scene a freedom which the rest of the film would dearly love to have, weighed down, as it is, by clumsy sub-plots, vendettas, old alliances and new loves.Let me declare my biases: I like Bond films. I particularly like Daniel Craig as Bond. When, in Skyfall – once again in an opening sequence – he boards the train, protects himself from being shot by climbing into the cabin of a front-end loader on a float car and then, miraculously, delightfully, thwarts his enemy’s ploy of disengaging the railcars by grabbing the carriage in front with the arm of the aforementioned metallic beast, ripping half its roof off in the process, when he has crawled up the arm and dropped down into the passenger car, full of tremulous innocents, he straightens up, stops for a moment. He stops to adjust his jacket and to shoot his cuffs. Only then does he leap forward to continue pursuing his enemy. That moment is, in my mind, worthy of the whole rollicking, enormous, over-priced, over-blown, worn out franchise.The problem with that film, Skyfall, and, even moreso, with Spectre, and I think I can talk about this without giving spoilers, is that the plots are asinine. Not because Bond survives where several hundred others (including the arch-enemy and a couple of beautiful women) die. That’s never really been the issue; we’re in the business here of the voluntary suspension of disbelief. The problem is that the stories have become centred around Bond himself. The evil genius who is bent on world domination, in these new iterations, is not surprised or even dismayed to find Bond at his heels, interfering with his plans. Bond is, rather, at the centre of his plans. Bond is his raison d’etre, Bond is the kernel of pain at the core of his existence. Elaborate back stories are woven to create this, adoptions, substitutions, mentorships. But this focus on him as the familial member who must be overcome on the path to world domination – as if, in fact, world domination is secondary to humiliating Bond, detracts from the enjoyment in the films in such a profound way that it is all but impossible to put disbelief aside.I don’t want to discover that Bond knew the arch-villain when they were children and one or other of them offended someone. I couldn’t give a rat’s arse to be honest. I’m not in the cinema for a psychological assessment of childhood hurt and how it has given rise to the present villain or the present Bond, I’m there to be blown away by the sheer grandiose hubris of the villain’s plans, his or her delusions of grandeur which should be, it must be said, fantastic, overblown, and slightly scary. I’m here to see Bond, against all odds, foil these plans and rescue the girl (although, it must be said, in this new film the girl has at least some agency, which is a great relief).What has happened recently in the series is that the requirement for an ‘origin story’ has overtaken the genre under the rubric of what Hemingway referred to as ‘the trauma theory of literature’. As I said a moment ago, who cares? Bond films are not literature and we don’t want this guff pasted on them in the hope of making them so. Bond is not a character we love because he was badly treated as a child. We love him because he knows how important it is to be well dressed when dropping into a train carriage, or going into a bar, a ballroom, or a battle. Cut the nonsense please, and give us some real nonsense instead.

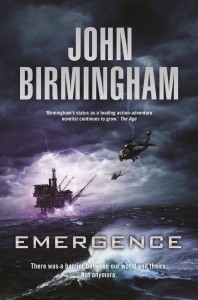

I have just finished the third instalment in John Birmingham’s Dave Hooper Trilogy: Emergence, Resistance, Ascendance. I’m reading Birmingham, of course, because I’ll be interviewing him in a couple of weeks for Outspoken. Generally we don’t want to do too many repeat authors but I’d bumped into him at the Reality Bites Festival last year in Eumundi and in response to my casual question of what he was up to he told me he was publishing not one but three (3!) books in the first half of the new year, ‘Not the sort of stuff you write, Steven, sci-fi/fantasy.’ ‘Christ,' I said, 'No orcs, I hope.’ ‘God yes, orcs,’ he replied, ‘Well, not orcs as such, but monsters from the under-realms.’ When he saw the expression on my face he launched into his speil. ‘Listen,’ he said, ‘it starts out in the Gulf of Mexico, on a rig like the Deepwater Horizon. Dave Hooper’s the security officer and he’s been on a binge, blowing his annual bonus on alcohol, sex and drugs and he’s flying back out to the rig hoping to have a few hours to sober up when they get the call there’s been an incident… monsters are boiling up from the depths. Out on the rig Dave finds himself confronted by one of these things, raging drunk on the blood of its victims, and by chance whacks it with a splitting maul, killing it and thus transferring the energy and knowledge of the beast to himself… They have, you see, drilled too deep…’Now I had a conversation with a young person the other day about this sort of thing. She said, ‘As soon as someone in a book names their sword I’m out of there.’ Which pretty much sums up my own attitude. Dave’s splitting maul, in these books, is called Lucille. Enough, you’d think, to have me running. But Birmingham brings an intelligence to this sort of guff which is both unusual and fascinating. He’s long been a weapons afficionado: it’s not uncommon to find one of his characters cradling one or other piece of hi-tech materiel, indeed on his blog Cheeseburger Gothic at one time he had a long thread asking for opinions on how to make your way across the US after civilisation had broken down, what equipment would be required… and this had given licence to a whole army of libertarians and ex-military types to spend many thousands of words listing (or arguing with each other about the relative merits of) various guns, vehicles, rocket launchers etc.. What I mean to say is that Birmingham doesn’t mind blowing things up. He doesn’t shrink from murder and mayhem, in fact he seems to to take a particular pleasure in destroying whole American cities; these are action novels in the primal sense, but they’re also scenarios to play out aspects of humanity, both social and political in unusual ways. Dave Hooper, Super Dave, is deeply flawed and being given super powers doesn’t in any way deliver him from his inner demons. Those around him, who have to try to point his new abilities in a useful direction, often refer to him as a moron, which is probably not quite fair because he’s clever enough, while lacking, perhaps, emotional intelligence. The problem being that he has to work out his issues on the world stage while fighting an ever expanding horde of monsters. (One of the more curious powers he’s gained is an extremely powerful effect on women of child-bearing status)One of the keys to writing good fiction is the ability (sometimes very difficult) to remain true to the reality you have created. What this means is no explanations given, or none outside of the course of the narrative. If there are ravenous monsters boiling up from under the ocean (and many other places besides) then that is the world the story inhabits, the author has to have complete belief in his own reality. If for a moment that wavers then the reader, too, becomes lost. Birmingham never flinches. If anything he gets better over the course of the three books – one of my complaints about some of his earlier series were that they started off remarkably, extraordinarily, well but, as the story played out, became less interesting or plausible or something – whereas in these ones the ideas and scenarios only become more fascinating and entertaining. The third book, Ascendance (which, I guess it’s some kind of spoiler, doesn’t finish the story), is a real tour de force, the first fifty thousand words are all one set piece, taking place in the space of a single night in Manhattan. Reading it I was, in the first place, unwilling to put it down, but also in a state of awe at Birmingham’s capacity to sustain the narrative in a manner that levened the mayhem with an unfolding of Dave’s understanding and his relationship to those around him, cut with wry comments on society as a whole, throwaway lines that chart the course of western civilisation in less than fifty words, or which turn the characters back on themselves and our perceptions of them. I’m not going to detail the plot or give away any more spoilers, but I will say it appears that I’ve been guilty of false advertising in my promotion of this Outspoken event by including in the blurb the statement: ‘none of this waiting a year for the sequel with our Mr Birmingham,’ because clearly there is going to be a sequel. Never mind that I can’t wait for it... I'll have to. Outspoken presents: A conversation with John Birmingham. And, introducing, Andrew McMillen, author of Talking Smack. Maleny Community Centre, July 22, 6 for 6.30pm. Tickets $18 and $12 for students, available from Maleny Bookshop 07 5494 3666 for more info visit Outspoken

I’m not going to detail the plot or give away any more spoilers, but I will say it appears that I’ve been guilty of false advertising in my promotion of this Outspoken event by including in the blurb the statement: ‘none of this waiting a year for the sequel with our Mr Birmingham,’ because clearly there is going to be a sequel. Never mind that I can’t wait for it... I'll have to. Outspoken presents: A conversation with John Birmingham. And, introducing, Andrew McMillen, author of Talking Smack. Maleny Community Centre, July 22, 6 for 6.30pm. Tickets $18 and $12 for students, available from Maleny Bookshop 07 5494 3666 for more info visit Outspoken

The Guardian has invited several writers to give their rules for writing fiction. The list includes Elmore Leonard, addressing the perils of adverbs, Hilary Mantel, Richard Ford (marry someone who likes the idea of you being a writer) and many more, to be found here.

The December 17th issue of the New York Review of Books has an article from John Lanchester about Nabokov’s posthumous novel, The Original of Laura.In it Lanchester discusses the difference between an author’s signature and their style, and, as a way of explaining this he writes:

‘One example might be from one of Nabokov’s most famous flashes of brilliance, Humbert Humbert’s memory of his mother in Lolita: “My very photogenic mother died in a freak accident (picnic, lightning) when I was three.” It’s hard not to be dazzled by the parenthesis, which is pure signature; but the heart of the sentence, its moment of style, is in the quieter and much less prominent word “photogenic.” You realize that Humbert knows his mother only from photographs. The sentence’s quiet poetry is the poetry of loss.’

I struggle to express how profoundly such a piece of writing moves me. Firstly the Nabokov, which I naturally love, as if his use of words is already part of the mechanism of my blood flow, and reading them again makes it quicken. But then secondly with Lanchester’s analysis of why it moves me, which I had never previously understood. This is the thing, I guess. As a reader, some might say a compulsive reader, since my early teens, I both consume words (and produce them), without really knowing how or why one piece moves me and another does not. I’ve tried to understand it but I don’t think intellectualising necessarily helps. What I’ve learned to do is to trust the quality of resonance which sentences generate within me when I read them or hear them. My own or someone else’s.Occasionally though, I stumble upon examples which are so extraordinary that a certain amount of analysis is essential. Here is one that I recently found in Alexsandar Hemon’s Love and Obstacles:The story is called ‘Good Living.’ The narrator is Bosnian, he is selling magazines door to door in Chicago, the outer suburbs:

This is the thing, I guess. As a reader, some might say a compulsive reader, since my early teens, I both consume words (and produce them), without really knowing how or why one piece moves me and another does not. I’ve tried to understand it but I don’t think intellectualising necessarily helps. What I’ve learned to do is to trust the quality of resonance which sentences generate within me when I read them or hear them. My own or someone else’s.Occasionally though, I stumble upon examples which are so extraordinary that a certain amount of analysis is essential. Here is one that I recently found in Alexsandar Hemon’s Love and Obstacles:The story is called ‘Good Living.’ The narrator is Bosnian, he is selling magazines door to door in Chicago, the outer suburbs:

‘My best turf was Blue Island, way down Western Avenue, where addresses had five-digit numbers, as though the town was far back of the long line of people waiting to enter downtown paradise. I got along pretty well with the Blue Islanders. They could quickly recognise the indelible lousiness of my job; they offered me food and water; once I nearly got laid. They did not waste their time contemplating the purpose of human life; their years were spent as a tale is told: slowly, steadily, approaching the inexorable end. In the meantime, all they wanted was to live, wisely use what little love they had accrued, and endure life with the anaesthetic help of television and magazines. I happened to be in the neighbourhood to offer the magazines.’

The first time I encountered this passage I had to stop and read it four times, and then ring up a friend and read it to him aloud, twice, over the telephone, before I could begin to think about continuing my life.Take, ‘As though the town was far back of the…’ This ‘far back of’ is a peculiarly American use of English, here used by someone writing in their second, adopted, language. Its unusual word order, the extra ‘of’, seems to deliberately push the suburb further back in the sentence, further away from the place where the numbers were smaller, where (apparently) paradise is.But it turns out that it’s not just onomatopoeic in its placement. It’s also elegant. If I was writing the sentence I would probably have started by trying: ‘as if the town were a long way along, no, cross that out, can’t have a long way along, well then, a long way down, or, a long way towards the back of the long line,’ all of which are unsatisfactory. So I’d rewrite it and rewrite it, and eventually start to question if that was what I really wanted to say when I couldn’t get it to work, perhaps break it up into two or three sentences or try to come up with a different metaphor. It is unlikely I’d have stumbled upon Hemon’s solution: ‘as though the town was far back of the long line of people waiting to enter downtown paradise.’But then he goes on: ‘They did not waste their time contemplating the purpose of human life; …’ This was the sentence I wanted my friend particularly to hear when I called him up but he got lost in the throwaway line, ‘once I nearly got laid,’ and the story that spins off from there. So I had to read it to him twice:

‘their years were spent as a tale is told: slowly, steadily, approaching the inexorable end. In the meantime, all they wanted was to live, wisely use what little love they had accrued, and endure life with the anaesthetic help of television and magazines. I happened to be in the neighbourhood to offer the magazines.’

Here is writing of an extremely high order. When I read something like that I feel as though the game is up. We may as well all go home, Beethoven is amongst us, what’s the use?